In my role as co-chair of the Treasury History Network, earlier this year I gave a lecture looking at the history of the Treasury’s buildings over the past 350 years. Of all the things that could be said about the Treasury, why focus on its buildings? For a number of reasons.

First, because even though the Treasury is one of the oldest institutions of the state, it is not readily identifiable with a single building. Despite its longevity, the Treasury has been a bit of a Whitehall nomad: it has moved around repeatedly over the centuries, often in response to unexpected events like wars and fires, but has never gone very far – at least until its recent expansion to the Darlington Economic Campus.

Mario on some of the ground occupied by the original Treasury Chambers in Whitehall Palace, between the MoD building and 61 Whitehall

Mario on some of the ground occupied by the original Treasury Chambers in Whitehall Palace, between the MoD building and 61 Whitehall

Second, because the relatively unknown and seldom-told story of the Treasury’s buildings highlights the impact that the working environment can have on our institutions. In the civil service, we all work on different policies and programmes, for different governments, at different times. This makes our buildings some of the clearest reference points for our collective memory.

Chronology of the Treasury’s buildings

The history of the Treasury can be traced back – sometimes faintly, sometimes clearly – for nearly 1,000 years. While there is evidence of revenue collection and distribution during the Anglo-Saxon period, it is only after the Norman conquest that we see the reference to “Henry the treasurer” – the official charged with administering the royal treasure – in the Domesday Book of 1086.

In the centuries that followed, the treasurer and the Exchequer were located together in New Palace Yard, next to Westminster Hall. In the 16th century, after a fire in the Palace of Westminster destroyed the chambers of King Henry VIII, he moved into a property just up the road. By 1536, this had become Whitehall Palace, the official residence of the monarch. In the 1660s, the Treasury separated from the Exchequer and moved into Whitehall Palace.

These are the first rooms used by the Treasury as a separate institution. The original Treasury Chambers were on the ground floor of the Privy Gallery building in Whitehall Palace, a location that I have been able to locate in present-day Whitehall. But the Treasury did not occupy these chambers for long. Because in January 1698, a huge fire destroyed most of Whitehall Palace, including the Treasury Chambers. The work of the Treasury moved into a building formerly used as a cockpit (an arena for cockfighting) on the park side of the palace. By the 1730s, this building was in terrible condition and architect William Kent was commissioned to build a replacement on the same site. Kent’s building, completed in 1736, was the first purpose-built Treasury building. It is still there today, on the southeastern corner of Horse Guards Parade.

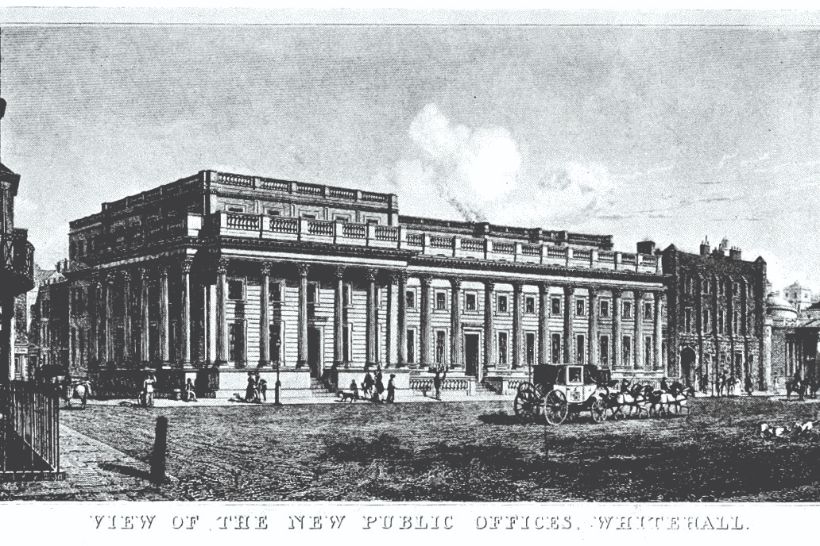

Over time, more space was needed. In the 1820s, architect John Soane was commissioned to build offices connected to Kent’s Treasury, but on the Whitehall side. His building, over budget and not well regarded, did not last long: in the 1840s, architect Charles Barry was given the job of updating it.

John Soane’s Whitehall building (1820s) known as “New Public Offices” but linked to William Kent’s Treasury behind it

John Soane’s Whitehall building (1820s) known as “New Public Offices” but linked to William Kent’s Treasury behind it

Barry extended the building along Whitehall, added an additional storey, and improved the frontage. This building became known as the New Treasury Offices – although we now know it as 70 Whitehall – and was occupied by the Treasury and three other government departments.

70 Whitehall, known as New Treasury Offices when it was built by Charles Barry in the 1840s

70 Whitehall, known as New Treasury Offices when it was built by Charles Barry in the 1840s

WWII and the Treasury

Over the centuries, the Treasury’s policies have often been shaped by the financial imperatives created by war: the introduction of a “temporary” income tax after the Napoleonic Wars, or the abandonment of the gold standard at the outbreak of the First World War. The same is true about its buildings. In October 1940, during the Blitz, German bombs damaged the Treasury building on Whitehall. This meant that the majority of Treasury staff had to relocate to Government Offices Great George Street, or GOGGS, on the corner of Parliament Street and Great George Street – where HMRC and HM Treasury are located today.

In 1940, GOGGS was already a busy building, with many ministries located there as part of the war effort, so the Treasury had to jostle with other government departments for space. The Air Ministry was one of the largest occupants at the time and had use of some of the nicest rooms. The Air Council used the large room on the second floor on the north side of the building – this room eventually became the office of the chancellor of the exchequer between the 1950s and the 2000s.

The October 1940 air raids also damaged Downing Street and the prime minister, Winston Churchill, had to relocate. In December 1940, he and his wife moved into a set of rooms in GOGGS repurposed for their use. They were on the ground floor facing St James’s Park. These rooms became known as the “Downing Street Annexe” – which the Churchills lived in until the end of the war in 1945.

“1 Horse Guards Road now feels like an open and efficient modern office. This has transformed the way the ministry operates”

Churchill was not the only celebrated occupant of GOGGS during the war. It was around this time that one of the most famous economists of all time – John Maynard Keynes – worked at the Treasury as an unpaid adviser to the chancellor. The exact location of his office in GOGGS has long been a mystery but, as part of my research, I have been able to locate it. It is now an open-plan office used by HMRC colleagues.

In the decades following the war, the Treasury ended up as the biggest tenant at GOGGS and occupied the space around the circular courtyard and the centre of the building, with the Treasury entrance on Great George Street.

Post-war decline and revival

By the 1990s, GOGGS had fallen into disrepair. A number of schemes for refurbishment were considered, but it was only in 1999 that the project got the go-ahead. Between 2000 and 2002, Treasury staff squeezed into the eastern end of GOGGS facing Parliament Street (plus some spillover in a tower block in Victoria) so that work could start on the western side of the building facing the park. The Treasury then moved into the newly refurbished section of GOGGS – renamed as 1 Horse Guards Road. The refurbishment of the eastern side of the building then followed and was completed in 2004.

GOGGS today, the 1 Horse Guards Road entrance

GOGGS today, the 1 Horse Guards Road entrance

Beyond London, the Treasury has had a longstanding link with Norwich, dating back to its responsibility for the Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency and then the Office for Government Commerce, which in 2000 became part of the Treasury Group. The idea of a Treasury office in the north of England was first floated in the run-up to the 2019 general election. The following year, chancellor Rishi Sunak announced the intention to create a Treasury outpost in the north, just around the time that the Covid pandemic forced a range of employers to introduce hybrid working.

Then-permanent secretary Sir Tom Scholar explained that “it was of course entirely coincidental that the pandemic happened just as the Treasury was starting to plan the new office outside London. But in retrospect, the experience of working remotely through the lockdown was critical in helping the department make a success of the new office.”

Feethams House, Darlington Economic Campus, which today houses more than 300 HMT officials

Feethams House, Darlington Economic Campus, which today houses more than 300 HMT officials

In spring 2021, the chancellor announced that the chosen location for the northern campus would be Darlington. The Treasury initially moved into a building called Bishopsgate House, sharing accommodation used by other government departments already located there. In 2022, Treasury staff in the Darlington Economic Campus moved into Feethams House. Plans are progressing for a move into purpose-built offices in Brunswick Street in 2027.

Lessons for today

After the House of Commons was destroyed in the Blitz in 1941, Churchill said that “we shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us”. What does the history of the Treasury’s buildings tell us about the institution?

1. Exchequer Receipt Office, New Palace Yard Westminster; 2. Treasury Chambers, Whitehall Palace; 3. The Cockpit, Whitehall Palace; 3. William Kent’s Treasury; 4. Treasury Buildings; 5. Government Offices Great George Street; 6. 1 Horse Guards Road

1. Exchequer Receipt Office, New Palace Yard Westminster; 2. Treasury Chambers, Whitehall Palace; 3. The Cockpit, Whitehall Palace; 3. William Kent’s Treasury; 4. Treasury Buildings; 5. Government Offices Great George Street; 6. 1 Horse Guards Road

First, it explains the importance of geography to one of the central relationships in Whitehall: that between the leader of the government and the Treasury. At the turn of the 18th century, the most important source of political power stemmed from the ability to control the financial machinery of government. One of the reasons Downing Street became the official residence of the prime minister is because of its proximity to the Treasury – which at the time was located in the Cockpit, and then William Kent’s building on the same site.

Second, it tells us something about how the physical environment can affect institutional culture. The Treasury entered GOGGS at a time when the building was literally a bunker. In the years that followed the war, a closed and suspicious approach became central to the way the department operated. The 2000-2004 refurbishment created a distinctly new working environment, which promoted openness and collaboration. Some 20 years after the refurbishment, 1 Horse Guards Road now feels like an open and efficient modern office. This in turn has transformed the way the ministry operates as an institution.

Third, it shows the importance of having a broader national footprint. The Darlington Economic Campus houses more than 1,000 officials from across departments, of which more than 300 are from HMT. As an institution, our presence outside of London has never been this significant. It changes the way we do our work by providing a gateway to better policy innovation, diversity of thought and new stakeholders. It has enabled an active engagement programme to exchange views and perspectives with businesses in the region and has given the Treasury access to a wider set of labour markets.

These are just some of the stories and lessons that we can take from the remarkable history of the Treasury’s buildings over the centuries, but there are many more that I hope to tell over time.

Mario Pisani is a deputy director at HMT