A deep dive into the Spending Review 2025 documents to fish out the details that matter to civil servants. Words by Tevye Markson, Jim Dunton, Suzannah Brecknell and Beckie Smith

Earlier this summer, chancellor Rachel Reeves set out her plans for public spending over the next five (or so) years in the UK's first multi-year Spending Review since 2021. Here, CSW sets out the key takeaways.

The picture is one of rising spending, but a continued squeeze on day-to-day budgets for almost all departments.

The Treasury is describing this Spending Review period as containing two phases. The first includes the current and previous financial years – budgets for this phase were set by Reeves last summer in her first big speech as chancellor. The second phase runs until April 2029 (for day-to-day spending, or RDEL) or 2030 (for capital investments, or CDEL).

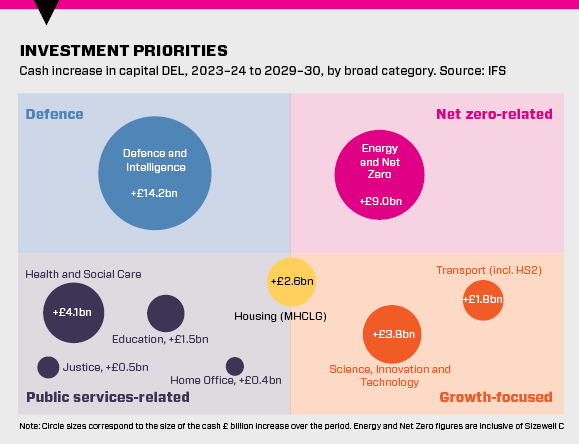

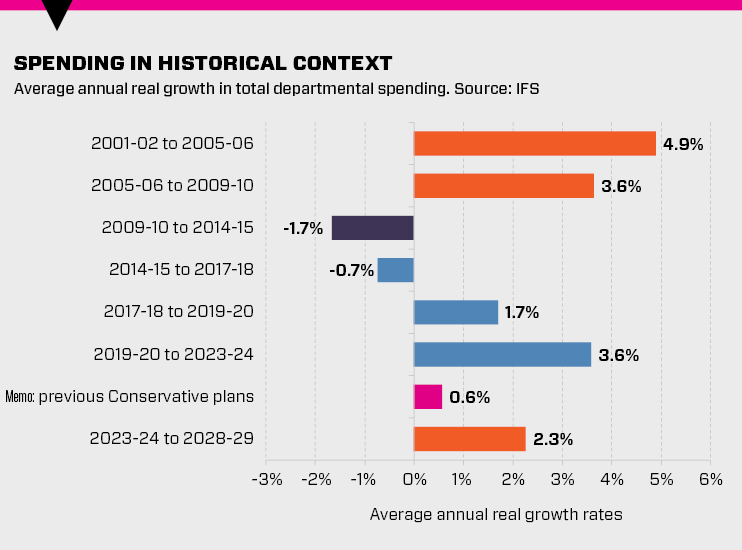

Over both of these phases, public spending is set to grow at an average of 2.3% a year in real terms. This rise is mostly driven by big capital investments – which will grow by 3.6% a year, compared to 1.7% for day-to-day spend. These investments reflect the chancellor’s focus on security, energy and growth, while in public service-focused investments health took the largest share.

The growth in day-to-day spending has been weighted towards the start of the Spending Review period – total RDEL rose 2.6% last year and is due to increase by 2.5% this financial year, compared to 1.8% in the next financial year and 1% in each year after that. It is also mostly directed at the health service which, though it does not have the largest rise proportionately, accounts for some 90% of the increase in revenue spending, thanks to its total size overall. This tapering of increases combined with continued growth in demand for many services means that, despite growing public spending, departments will need to improve their efficiency and productivity if they are to meet both budgets and demand over the next five years.

The SR25 document sets out three key principles which the Treasury is advocating to create a more “agile and productive state”: digitising, creating a cost-conscious culture and building a leaner, higher-skilled civil service. Departments have been tasked with delivering reductions of at least 11% in real terms by 2028-29, according to the SR25 documents, and 16% in real terms by 2029-30. This is expected to save £2.2bn in 2029-30. Alongside this, departmental efficiency plans outline how they will save £14bn in total over the spending review through largely workforce, estate and digital reforms. The document also set outs that the government will aim to drive public service reform according to three key principles: integration, prevention and devolution.

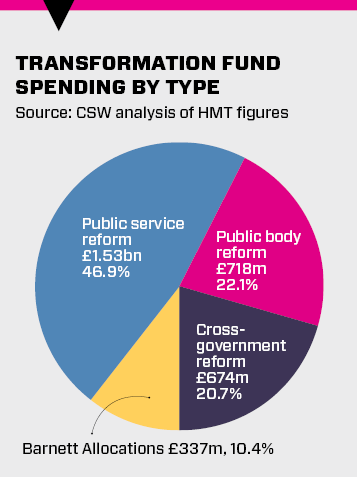

These principles may be high level, but a £3.25bn Transformation Fund – first announced in the Spring Statement in March but with more details of allocations announced at the Spending Review – provides a more concrete example of how the Treasury is prepared to support change, and which changes it is prioritising.

In this SR25 deep dive, we explore the details of departmental efficiency savings, look closely at the Transformation Fund, and consider how the Green Book could be changing to support government’s pledge to become less London-centric.

Before we get there, a word of caution. The Spending Review provides much-anticipated stability for public spending, but it doesn’t mean that we won’t see shifts in the years ahead. While the chancellor has changed – and loosened – her fiscal rules to enable this growth in spending, low and unstable economic growth means it’s likely she will need to make adjustments to either public spending or tax levels before the end of the parliament. Changes in policy may also spark shifts in budgets or taxes – as we will see at this year’s Autumn Budget, when Reeves has said she’ll explain how changes to winter fuel payment eligibility will be funded.

Speaking at a briefing event the day after the Spending Review, outgoing Institute for Fiscal Studies director Paul Johnson said that if tight spending plans in the last year of the parliament “aren’t topped up at some point, I’ll be very surprised indeed”. Pressure is likely to come from health and defence, he said, which could mean that other departments see an even tighter squeeze ahead.

Day-to-day spending

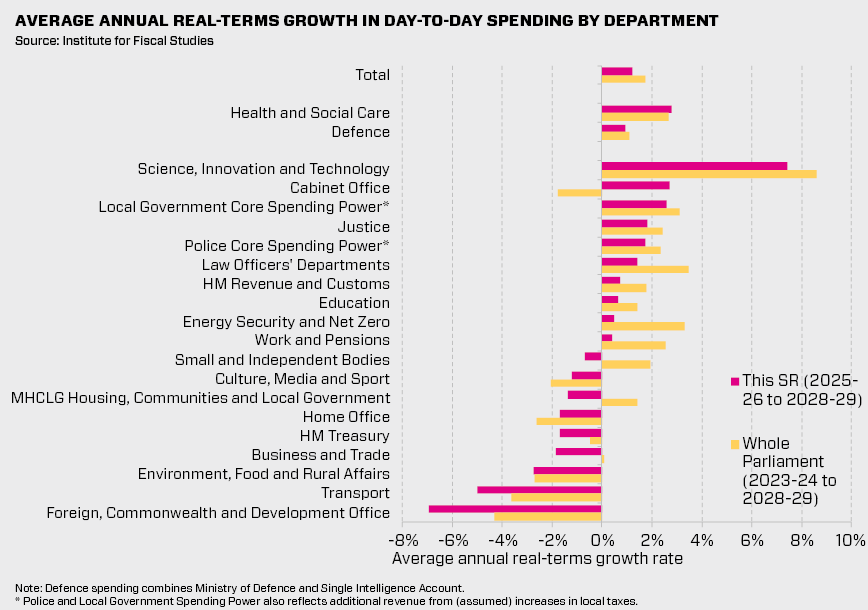

Pre-briefings and news coverage of the Spending Review focused on the relatively generous settlements for health and defence – understandably, since these massive services constitute a large chunk of public spending overall. But if you consider the settlements in proportion to departmental budgets, the most generous rise goes to the science department.

This increase in part reflects machinery of government changes. But it also reflects DSIT’s role in delivering some priority areas for the government: digital public service reform, its oversight of research and innovation funding – which has increased overall – and support for key growth areas such as life sciences. The department is receiving an extra £1.9bn in total spending to drive digitisation across government, as well as £2bn to implement the government’s AI Opportunities Action Plan.

The £1.9bn will cover, according to the SR document, the rollout of new products and services such as the GOV.UK Wallet and App, productivity-enhancing AI tools across the public sector, and the replacement of legacy systems.

Education, justice and local government also receive real-terms increases over the whole parliament, with the largest reductions in the FCDO – thanks to cuts in the Overseas Development Assistance budget – and transport – thanks to the removal of rail subsidies.

Analysis from the Institute for Government shows that even among the “winners” there will be challenges ahead: only three areas – local government, courts, and general practice – have funding that exceeds expected demand growth by more than 1%.

Best-laid plans: How were Departmental Efficiency Plans developed, and what do they tell us?

It’s not unusual for governments to factor expected savings into their spending plans – in fact, most civil servants will have no experience of a spending review that didn’t bake in budget reductions in some form, usually in the “administrative” budgets which cover the running of central departments.

It is less common for details of those savings to be set out alongside spending plans, but among the documents published after the chancellor sat down in the Commons was a more than 40-page Departmental Efficiency Plans report that did exactly that – up to a point.

The document was published by the Office for Value for Money, set up in autumn 2024 to help departments identify 5% efficiency savings, which would be repurposed towards priorities.

Six months after the OVfM’s creation, Treasury permanent secretary James Bowler explained that at least 3% of these savings would be technical efficiencies – meaning that departments would be delivering more output for the same input, or the same output for less input, rather than stopping activities (reducing outputs). The intention is that this will maintain or improve the quality of public services while driving up value for money.

In the run-up to the multi-year spending round, OVfM worked with departments to set “bespoke targets underpinned by credible plans”, according to its final report published alongside the Spending Review. It set a minimum expectation, based on wider good practice, of delivering 1% efficiencies per year over the SR25 period. This was subject to agreeing bespoke targets with departments based on their specific circumstances, including the availability of investment to drive efficiencies, the types of opportunities available within the department, and the extent to which departments could draw from existing plans. The credibility and deliverability of these plans were assessed by the cross-government functions, including the government commercial function, the Office of Government Property and the government grants management function.

The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, as the digital centre of government, provided guidance and support to departments on their plans for delivering efficiencies through digital transformation. According to the Spending Review and OVfM documents, as a result of this process, all departments found a minimum of 5% in total efficiencies, with average day-to-day technical savings of 4% (though four departments have not yet hit the target of 3% technical savings). These efficiencies are expected to deliver savings worth £14bn across the Spending Review period. This exceeded the initial expectation of £12bn efficiencies by 2028-29. The OVfM identified three common areas of focus for departmental plans: digitisation and automation, workforce reforms and estates rationalisation.

Workforce

Much of the focus in the efficiency plans is on workforce reforms to make departments leaner and more agile. The Treasury, for example, says it will get smaller and introduce a more flexible resourcing model that is “more efficiently in line with ministerial priorities”, while the Ministry of Justice says a more agile workforce will mean it is able to swiftly react to emerging priorities. Going in the opposite direction, the FCDO says it will reduce the number of staff in flexible resource pools.

Many departments mention reducing the use of consultants and insourcing services – particularly specialist digital roles – and DESNZ says building in-house expertise in key corporate functions could reduce costs by 40-60%. Most plans also say AI will enable them to make better use of their workforce, with HMT going further by saying it will “allow central resources to be scaled back”. Only the Department for Transport mentions becoming more skilled, although several other plans talk about improving capability.

Some of the plans also describe structural changes such as widening managers’ spans of control and cutting back on layers of leadership to reduce managerial overheads, streamlining back-office functions, reducing the number of directorates, and streamlining the size of their senior civil service cadre. Others mention reforming grading structures and pay scales. Defra is the only department to explicitly set out the proportion of civil servants it plans to lose – and its 5% reduction target is only for 2025-26. The document says “making the civil service more efficient and effective is a key mission for the government” and that the Government People Group “will support departments through workforce reform and funded exits”.

Digital and artificial intelligence

Most of the efficiencies in this category involve using technology to either fully or partly automate routine, time-intensive tasks such as checking simple errors, note-taking, summarising reports, comparing different versions of texts, standardising formatting, and drafting documents. The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government estimates using AI to expedite routine tasks will save it 500,000 hours of staff time per year, while DESNZ expects AI to bring in non-cash workforce productivity benefits of £19m per year by 2028-29 by helping with everyday tasks.

Most plans don’t extend beyond these routine tasks, but DESNZ said it is exploring uses of AI beyond administrative tasks – in planning, consumer-facing activity, counter-fraud work, and policy design and consultation – and DSIT said it will “explore more ambitious opportunities to reimagine the way the department operates”.

Estates

Across almost all departments, estate reforms include a strong focus on reducing the London footprint, as the government aims to reduce the number of civil servants working in London by 12,000. But there are also plans to make better use of the buildings that government will still occupy.

The Treasury said reducing its presence in London will bring savings of £1.5m per year by 2028-29. The department said it has also found £1m in savings from accommodating the new National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority in its existing office space. The Department for Transport’s plan to rationalise its London estate, meanwhile, also involves expanding its presence in Leeds and Birmingham. To support this twin reform of relocating roles while building a new profile of departmental presence across the country, the Spending Review allocated £244m to complete the development of new government hubs, including the Darlington Economic Campus, the Manchester First Street Hub and the York Central Hub.

What next?

The four departments that have not yet developed plans to deliver 3% efficiencies by 2028-29 have been asked to continue identifying opportunities for further savings during the SR25 period, and the FCDO will also lead work on driving efficiency across the Official Development Assistance budget, which was excluded from the process, given recent significant changes. In line with a recommendation from the OVfM, the government has committed to an expectation of at least 1% technical efficiencies for all departments in all future years. To support this commitment, it will publish bespoke departmental efficiency targets and plans biennially. The government has also accepted the OVfM’s recommendation to introduce a programme of thematic value for money reviews in the years in between spending reviews.

Benjamin Paxton, senior researcher at the Institute for Government, said the publication of the Departmental Efficiency Plans is “a welcome move away from a past tendency to pencil in blanket savings without realistic plans to deliver them”. But he said the plans are “still relatively high level” and questions remain about how they will directly lead to savings or better outcomes. “What investment is needed to realise these efficiencies? Where exactly will the savings be found? And how will departments be held to account for delivering them? From the plans alone, it’s difficult to tell whether the proposed £14bn of savings are achievable, which makes strong accountability for delivering them crucial,” Paxton said.

Gareth Davies, the head of the National Audit Office, praised the process, saying: “Ensuring that efficiencies represent genuine improvements as opposed to spending cuts, developing clear plans to support targets, and ensuring rigorous follow-up of progress, are all important principles for achieving sustainable efficiencies.” But he said the “ultimate test” of departments’ plans will be their ability to deliver against the efficiency commitments: “We have seen too often in the past that planned efficiency savings fail to materialise.”

Transformers: Why the Transformation Fund matters, and what it’s being spent on

At £3.25bn, the Transformation Fund is far from the largest allocation of money in the Spending Review, but the government will be hoping its impact is far greater than its size. Certainly the fund is already attracting attention – and approval – from government watchers. Speaking on the IfG’s weekly podcast, senior fellow Giles Wilkes described it as “just the sort of thing we’d have been calling for”.

Doing things more efficiently often requires putting in money first, he continued, and “that’s really, really hard to do” within government. So to have “found an institutional mechanism to do that could be really exciting,” he said.

The fund, administered by the Treasury, was originally announced at the Spring Statement, but we now know how all of the money will be allocated. Just under half is being given to public services themselves – from £23m allocated to recruit extra foster families to £760m to reform the SEND system. These allocations reflect some of the public service reform principles set out in the Spending Review documents: £100m has been allocated to community help partnerships which, according to the Treasury, will “bring together a range of services, providing better support for adults in crisis and reaching vulnerable individuals earlier, before problems escalate”.

Early intervention is also explicitly mentioned in the £557m which will support reform of children’s social care to “help more children stay with their families, ensuring families have timely support and fixing the broken care market”. The next biggest category within the transformation fund is a total of £718m over three years which will finance reforms within individual public bodies – such as improving HMRC’s customer services, implementing the Post Office’s strategic plan, or reforming the asylum system.

A little less – £674m over three years – has been allocated to cross-government reform programmes. This includes £323m over three years to support digital priorities, £143m in this financial year and the next to support civil service employee exit schemes; £117m over the next two financial years to drive shared services; and £50m given to the Cabinet Office over the same period to improve “workforce productivity, including to transform the model of civil service learning and development, and reduce dependency on costly external training provision”.

Green light: What changes are being made to the Green Book, and will they make a difference?

Among the changes announced by the chancellor in her Spending Review speech to the Commons, a commitment to change the Treasury’s guide on how to appraise policies, projects and programmes is unlikely to make a big splash with most voters. But if the changes have the desired impact, they might, according to Simon Kaye, policy director at the think tank Re:State, “even be the most important shift brought about by the Spending Review”.

Speaking to MPs, Reeves said she had heard concerns that “in the past, governments have under-invested in towns and cities outside of London and the south-east” and announced that a six-month review launched earlier this year would result in a “new Green Book [which] will support place-based business cases and make sure no region has Treasury guidance wielded against them”.

The review itself – published alongside the Spending Review – sets out plans to launch a new taskforce bringing together the Treasury, the communities and transport departments and participants from local and regional government to develop and implement an approach to building place-based business cases in the public sector.

The taskforce will be led by the Treasury’s second permanent secretary responsible for regional growth, along with the director general for local government, growth and communities in MHCLG and the director general for public transport and local group in DfT.

In a further signal of the need to involve local and regional government in the drive to improve how government appraises projects, the Treasury will be inviting mayoral strategic authorities to join its Green Book Network Steering Group. This board offers independent advice on appraising in the public sector and will be scrutinising the implementation of actions set out by the review.

"In all my experience in government, I’ve never seen a major project turned down by ministers because it didn’t pass the Green Book" – Dan Corry

As well as launching the taskforce on place-based business cases, the Treasury will also review Green Book guidance on transformational change to “help public servants to assess the potential of projects to bring about transformational growth more effectively”.

The department will commission an independent review of the Green Book discount rate – which aims to support comparisons of costs and benefits occurring over time – “to make sure that the government is taking a fair view of the long-term benefits that arise from transformational investments”.

Dan Corry, chief economist at Future Governance Forum, describes this review as “potentially radical”.

There are many who believe that “[for] a project which doesn’t produce benefits for quite a long time, but nevertheless is very important… at the moment, the discount rate is too high,” which means future benefits don’t carry enough weight. Whether the rate should change is the subject of some debate, he said, but he added: “I think it’s the right thing to review it, because they haven’t looked at it for some years”.

The Treasury has responded to concerns about over-reliance on benefit-cost ratios (BCR), which compare the costs and monetisable benefits of a policy, project or programme, and said that revised guidance will make it clear that these should not be used as a primary means of allocating funding.

Corry explains that BCRs are a poor way of assessing “non-marginal changes”.

Under the current rules, deprived areas are at a disadvantage when it comes to obtaining funding “because you’re going to need three or four different bits of investment to really build it up”, he says.

“If you assess each one individually, they might all look bad value for money, whereas if you put them all together, and you’re looking at the long term, they might well tick all the boxes,” he adds.

The review also commits to publishing business cases for major projects, and revamping Green Book training provided by the Treasury and the Welsh Government to address a lack of capability and capacity to develop and assess business cases across the public sector. It promises that a new “radically” shorter Green Book will be published at the start of 2026, with further changes to come as the place-based approach to business cases is developed.

While there is clearly potential for real change on the horizon, will it achieve the chancellor’s aim of supporting investment across the country? “By increasing the importance of some variables, reducing others, and introducing processes like place-based business cases, the basic terrain also shifts,” says Kaye. “The case for investment heading to different parts of the country is strengthened, instead of always being outgunned by London,” he said – noting that there have already been complaints about a relative reduction in capital investment in the capital.

He said the changes could, therefore, be an effective way to rebalance investment across the country. However, he noted that the proposed changes represent “a bit of an experiment” because “it’s easier to see the path to economic growth and other benefits” – yielding higher tax receipts – when weighting investment towards London and the south-east, as opposed to other regions. And he added that the Green Book “is not the Bible” and is often used to justify and explain spending decisions that have effectively been made anyway – and that any amendments will only affect meaningful change “if officials and decision makers actually shift their behaviour” in response.

Similarly Corry says he has “always been a bit sceptical that the Green Book… is the reason why we’re not getting as much investment outside London and the south-east, as a lot of people think we should”. Corry, who spent several years as a civil servant including as head of the No.10 Policy Unit and chair of the Council of Economic Advisers in the Treasury, added: “It’s much more a political decision. In all my experience in government, I’ve never seen a major project turned down by ministers because it didn’t pass the Green Book. And equally, there’s things that passed the Green Book that didn’t get done – so people exaggerate it.”

In a blog post published shortly after the review was published, Simon Dancer, a board member at the Institute of Economic Development, said the discussion around “the need to emphasise place-based analysis, the constant over-emphasis on BCRs, plus the long and complicated guidance” was “much welcomed”. But he said the publication of the review put paid to the idea – shared in some circles after the chancellor announced its launch in January – that the Treasury was planning to “completely rewrite the rules governing public investment orthodoxy”.

He pointed to the review’s finding that government’s approach to assessing land value uplift – the preferred method of assessing benefit from land and property schemes – “does not skew decisions in favour of more affluent areas, at the expense of less affluent areas”. He said it was “telling that after cutting through the smog, HMT have seemingly backed the core Green Book methodology (for built development schemes at least)” – though he stressed that this “does not diminish the [review’s] recommendations – which are to be saluted”.

This article was first published in the summer 2025 edition of CSW's quarterly magazine