I am grateful to Catherine Haddon for providing helpful information and deliberation from her Transitions report.

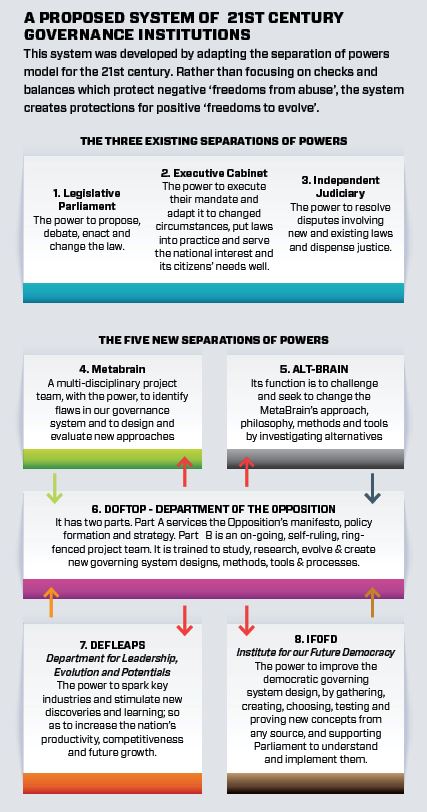

My article set out the need for and proposed location of an organisation which would provide rare new blood types and a catalyst to make our governing system more eco-systemic. I also set out a model of our legacy system and argued that a crucial task of any Department of the Opposition would be to reconfigure the legacy model. It did not have room to explore the wider system in which DOFTOP would sit – namely a new superset of interlocking umbrella institutions to unpick previous paradigms and catalyse change. These would include not only DOFTOP but a department charged with supporting growth and productivity by fostering key industries and innovations; an Institute for Future Democracy charged with gathering, testing and helping to implement changes to our governing system, a high level project team – which I’ve named the Metabrain - expected to identify flaws in our governance system and design new approaches to fix those flaws, plus a disagreeing counter-unit which would evaluate alternative ways to find and fix flaws.

My proposals (shown below) could be seen as radical. But major reform will not happen without an external catalyst, and I believe this is best initiated in a new Department of the Opposition. To increase the chances of this department improving the nation’s prospects, one of its crucial responsibilities should be to take upon itself the continuous search for governance evolution.

This task – a permanent part of DOFTOP’s work – would be performed by a specially recruited, trained, and self-organising project team, staffed with what I call ‘B-types’ – people who excel at creating disruptions to overturn present policy and conventions. This team of B types will neither be recruited by nor report to the teams providng support to the opposition party – instead they should be recruited by and should feed ideas into, the ‘Metabrain’ team.

The reformer’s task is to reach for systemic changes which will create those tomorrows, but some of the challenges that Dr Haddon raises are, I believe, lower order concerns which should not be allowed to prevent meaningful change. First we need to design a vision of the system we want to move towards, then define the system’s purpose, plan its development and specification and then finally consider HR issues such as the job descriptions and training requirements needed for suitable teams to work in that system. HR details do matter, at the appropriate time in the planning of a project, but not as reasons to prevent its planning from starting – we don’t stop the invention of new hardware or technology because new software and programmers will be needed.

Current fractures suggest cultural gaps still matter. The rejection of diversity and pluralism that motivated some to vote to leave the EU has caused great upheaval, and the referendum has revealed a deeply divided society, and one in which tolerance, respect and civility have been eroded. This is a governance problem and it needs radical reform to solve it. This sort of reform would normally be more likely to come from the opposition than the government, but I see no signs of it self-starting. I conclude that it must be provided from within a changed governing system; by specially selected and trained competing sets of project teams that no political party could presently invent unaided – even if they shared the need for their visionary work. It is a constitutional “concept car” type of exercise, that must be allowed to run its proof of concept work; until such time as its results are placed before select committees and MP’s in Parliament.to be debated and legitimised.

Meanwhile, the civil service is swamped by Brexit. Something more is urgently needed to ensure governance can evolve appropriately. At its best, opposition is timely innovation and adaptation. Such a task should have its own culture and appropriate skills; and not be diverted by present issues and approaches, or future political pressures – that is why a ring-fenced and, once set up, self-organising, ministry to provide such opposition is an urgent and essential part of my call for change.