Earlier this year, the secretary for science, innovation and technology, Peter Kyle, presented the ambitious AI Opportunities Action Plan which aims to not just prepare the UK for the artificial intelligence (AI) revolution but also for the country to have a key role in shaping it.

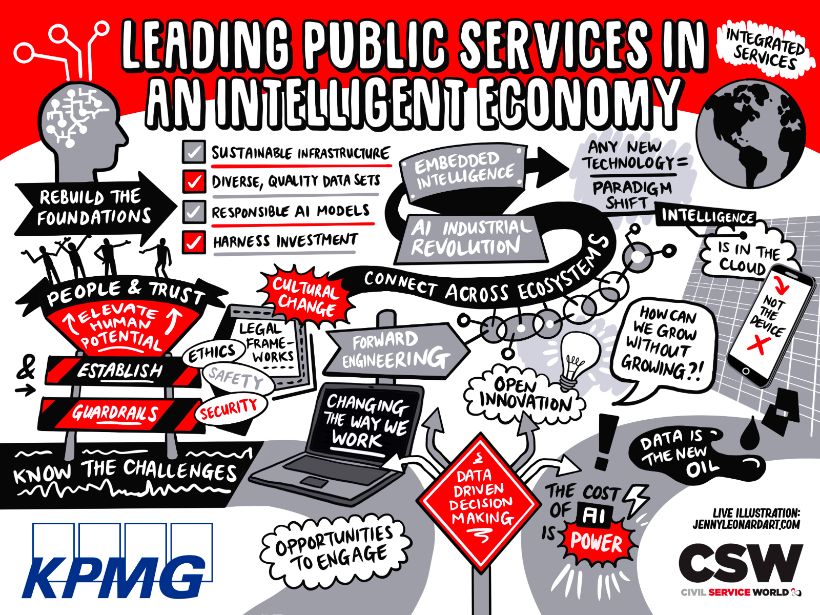

In a recent Civil Service World webinar, hosted in partnership with KPMG, experts from government, industry, and technology – keen to move beyond all the hype and hot air around AI – explored what it really means to lead public services in an ‘intelligent economy’ and what civil servants can do to prepare.

What is the Intelligent Economy?

Like the printing press, the steam engine, or even the humble light bulb, AI represents a significant technological paradigm shift. And with this shift, we can expect a transformational impact on public services as the tech becomes embedded into everything that we do.

But what exactly is the intelligent economy? Adrian Clamp, the global head of strategy & investment at KPMG, laid out the core idea: the intelligent economy is the next stage after the knowledge and digital economies. It is powered by AI – not just in individual tools and services but across the whole of our economic and societal systems. At its foundation are infrastructure shifts, new chips, greener and more scalable computing, and cloud-powered intelligence that allows even low-cost devices to act smart.

Making sure AI adds genuine value

AI is becoming part of everything. It is being embedded in workflows, organisational processes, as well as public service pathways, from processing tax and benefit claims to healthcare or licensing. This shift is not simply about popping in a chatbot – it is about redesigning how work in the public sector happens.

Illustration by Jenny Leonard

Illustration by Jenny Leonard

Karl Hoods, CDIO at DSIT and the department for energy security & net zero, described a practical approach from within government: layering digital delivery into three levels – core computing services, shared platforms that serve the majority of demands, and then the top layer of innovation.

Hoods adds that by learning from and understanding how different organisations use technology, the public sector can shape and improve its own processes.

Most importantly, Hoods said, his team is not chasing the shiniest or newest tool. Instead, they are identifying and matching problems to platforms, and then building around people, and looking for repeatable, high-impact opportunities where AI can genuinely add value.

The People Part: A Renaissance, not a revolution

The most important layer in the intelligent economy? People. Clamp argued that “we want to keep people really at the heart of all of this”. He said, AI should provide a renaissance of creativity, not simply a wave of automation. And by designing rewarding work, upskilling staff, and enabling the public sector to do more without simply growing its workforce.

AI may do tasks – but humans provide meaning. The goal is not to replace civil servants but to rethink roles, remove burdensome admin and tedious tasks, and allow people to focus on creativity, empathy, and problem-solving. Or, as Hoods described, sometimes the value of AI is freeing up time for two extra coffees a day – small mental breaks that reduce cognitive overload and help people return to work focused and ready.

Trust: A key pillar

Trust was a core theme throughout the discussion. Civil servants rightly carry a strong sense of responsibility, particularly when technology touches vulnerable populations or complicated ethical issues.

As Clamp noted, we must make sure that “trust is across the whole system”. The UK’s approach to AI safety, with its AI Safety Institute and global leadership role, is an asset. But trust must be built into workflows, choices of procurement, and governance structures, he added.

Heather Cover-Kus, the head of central government programme at techUK, pointed out that AI’s early reputation was shaped by fear but now it risks being overhyped. The answer is not embracing one of these attitudes or the other. It is ensuring that we have transparent, human-centric systems, and clear guardrails. It is making AI work for people – not the other way around.

Going with the flow

Another insight from the discussion was the shift from “use cases” to “flows”. A use case is a high-level description of how a system functions from an external perspective – defining the interactions between a user (or another system) and the system itself to achieve (or fail at) a specific goal.

Flows, on the other hand, examine the sequence of steps, decisions, and the actions involved in performing a process. The main flow represents the main pathway to success and then additional flows represent alternative pathways the user may take. For example, when there is a handling or user error.

Traditional digital programmes often focus on fixing isolated functions. Clamp said AI does not care about functions, nor does it work in silos. It performs best across workflows that cut across organisational boundaries – such as benefit claims, which that touch DWP, local councils, and the NHS.

Clamp explained that this “systems thinking” mindset – combined with agile, product-based approaches to delivery – is emerging as a key practice.

Reimagining skills and leadership

With any change comes a need for new skills – not just technical skills, but human skills.

Hoods said within the digital team they offer learning and development that is aligned with job roles, job families and the platform strategy. He said this strategy has been well tested. Within the rest of the organisation, Hoods explained, they partner across departments to create a better understand of capabilities. And they have been providing training opportunities at different levels.

Looking to the future, Hoods also said we could explore “leveraging the wider ecosystem of education”.

Cover-Kus added a provocative thought – should technology really be so complicated that we must train ourselves to use it? Good design should make tech intuitive. Once again, returning to people, perhaps our challenge is not always training people for tech but instead, insisting on tech that is made for people.

Building on this, Cover Kus said we should think beyond just digital skills and renew our focus on softer skills like communication.

Five key takeaways for civil servants

Think in systems, not silos – the intelligent economy will reward those who understand flows. Look at end-to-end citizen journeys and ask: Where can AI help us work smarter- not just faster?

Build trust – every use of AI is a chance to strengthen or weaken public trust. By embedding transparency, oversight, and accountability, we can build trust in processes and systems. We should aim for public confidence – not simply compliance.

Encourage curiosity and be critical – AI is often overhyped and sometimes poorly understood. Go beyond the headlines. Ask what these tools really do: Are they solving a genuine problem, or are they just shiny new toys?

Collaborate! Work with other departments, suppliers, universities, and communities. Share what you learn. Inspiration can be found everywhere.

Put people first, always. AI should make life better for both public servants and the public. If it doesn’t, why are we doing it?

Watch the webinar on demand