How has the leadership at the top of the civil service changed since Labour came to power and how does this compare to previous changes following an election?

It’s one year since Labour came to power after 14 years out of government.

There's been a lot of change in the leadership of the civil service since then, and the Institute for Government recently described Keir Starmer's administration as being “in the middle of a major reshuffle of permanent secretaries”.

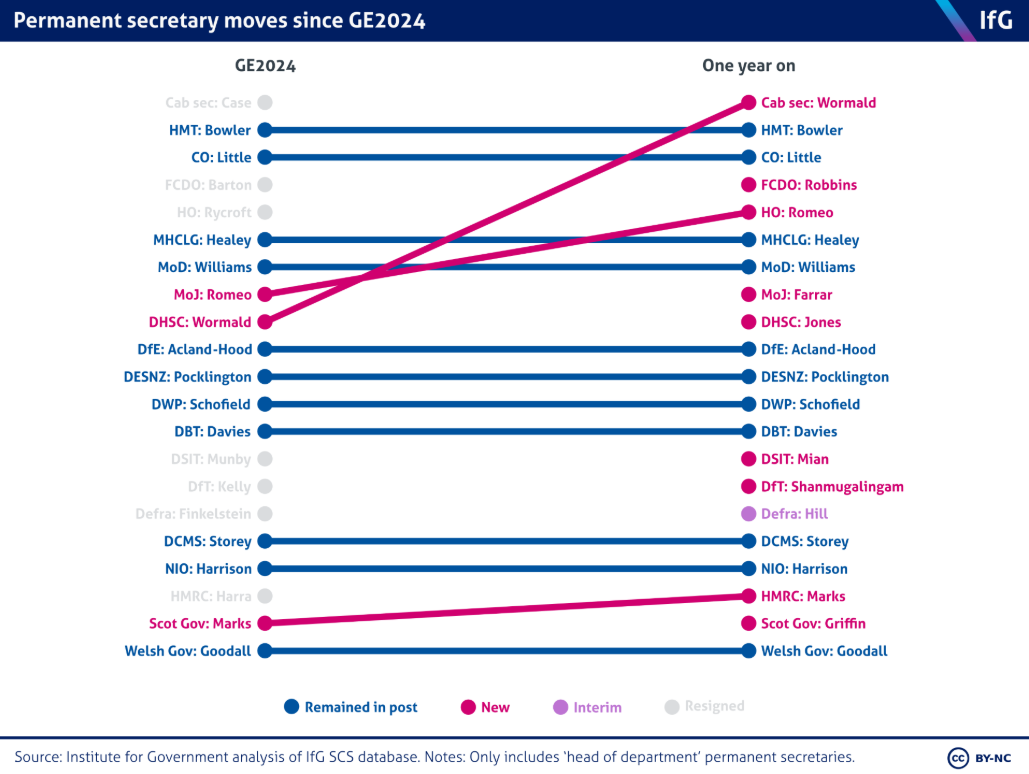

Seven perm secs have left government, while three have changed jobs within government and six new perm secs have been appointed – three of whom were returning to the civil service after stints in private or wider-public sector roles.

All this change means only 11 of the 21 perm secs in place when Starmer became prime minister are still in the same role.

But is this unusual? Here, we take a look at comparable moments of change in British government history, as well as outlining all the departures, arrivals and moves within government since last year’s general election.

And we also look at how the shakeup under Starmer compares to the upheaval in Boris Johnson's first year following his December 2019 general election win, (rather than from his first days as PM in July 2019) – an era much associated with perm sec sackings and dramatic resignations.

Is this level of overhaul unusual?

Comparing the change in Starmer's first year to that in similar recent major switches of power – the David Cameron 2010 Conservative-led coalition government after 13 years of Labour power and Tony Blair's 1997 government after 18 years out of power – it is clear that significant churn of perm secs in the first year is not uncommon.

In Cameron's first year as leader of the coalition government, seven perm secs left government – the same number as Starmer – while six moved jobs within government, double Starmer's total (although this includes an interim perm sec moving to become perm sec at another department). Eight stayed put, three less than under Starmer.

In Blair's inaugural year, eight perm secs departed – one more than under both Starmer and Cameron and, given the slightly smaller perm sec cadre at the time, this made for a higher porportion overall. Three perm secs moved jobs within government, the same as under Starmer. As with Cameron, eight perm secs stayed in their roles.

One shared characteristic of the first year of the Starmer, Blair and Johnson administrations – but not Cameron’s – is the cab sec leaving and being replaced by a perm sec from another department: from Case to Wormald under Starmer, Robin Butler to Richard Wilson under Blair, and Mark Sedwill to Case under Johnson. Gus O'Donnell, on the other hand, stayed in position for Cameron's first 19 months.

Prof Jon Davis, director of the Strand Group at King's College London, explains that after a long period in which one party is in power, it "makes sense that there is a rejig of the senior team".

Perm secs who have served under a previous government may have become associated with implementing particular policies or approaches to government, he explains. In the late 1990s, this change in approach was apparent in terms public spending, which had been declining through the Major years but then ramped up by the turn of the century. One former official described the change to Davis: "They said that, almost overnight, things changed. Previously, if you were somebody who was good at cutting in government, you had a big office overnight. In 1999 suddenly you didn't have the big office: it was the person who was good at spending. That massive splurge in spending and that focus on public services required a different kind of civil servant.”

Change can also be driven by the need for a good relationship between perm secs and secretaries of state – in the last year at least two perm secs are said to have left in part due to a failure to impress or gel with their new minister.

“Particular people find it more amenable with some people and some policies. So you've got some civil servants who rise under a Tory government in a way that they might not have risen under a Labour government and vice versa,” Davis notes. He recalls that former minister David Blunkett once told him: ”If I'm being told by the electorate to deliver world-class public services, I need a world class team that I pick.”

Considering the first year of Starmer's administration, Davis says he has heard from those inside government that much of the change is driven by a desire to bring on a new generation of officials.

“There was a level of perm secs who had been there for a while, and there's a number of younger ones who were ready to move up to the next level. So when you've seen quite a few leave over the past few months you're seeing not just a rejigging, but you're actually seeing new blood coming through."

He points as an example to the recent promotion of Emran Mian who is "seen as a very high quality choice, in a department which is rising in importance".

A recent blog from the IfG similarly suggested Starmer's shakeup of perm secs could be a good opportunity to drive change.

“Around half of core departments will have changed their leadership by the end of the year, which is an opportunity for secretaries of state to shape their top civil service teams with renewed energy for the tasks ahead,” said authors Alex Thomas, Heloise Dunlop and Teodor Grama.

Davis also notes that this kind of reset reflects a deeper issue around democracy and "the power of a popular mandate to come in and say, ‘We are changing things up. We want something different, and we've got a democratic mandate to do so’.

"If you've got this big mandate to ‘bring about’ change, and you don't see some change [among top officials] you could argue that actually the system, the bureaucracy, is becoming impervious to the popular will."

One move that Starmer hasn't made that several of his predecessors did in their first year is machinery of government or grading changes that necessitated a change in perm secs.

Cameron made Jeremy Heywood – who had been Brown's No.10 chief of staff – the first Downing Street perm sec on his first day in the job, adding an extra perm sec to his cadre. Blair, meanwhile merged the Department of Environment and Department of Transport into the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, which saw Patrick Brown depart and Andrew Turnbull move to the perm sec role at the enlarged department. And Johnson brought back the Downing Street perm sec job – bringing in Case from his role as the Duke of Cambridge's private secretary.

Style and substance

Numbers alone don't tell the whole story of how an incoming government can disrupt the civil service, of course.

Looking at the first year of Boris Johnson's government following his election victory in December 2019 (rather than from his first days as PM in July 2019), there were seven departures, the same as in Starmer's and Blair's first 12 months. A further three perm secs moved to different roles in government – the same as for Starmer and Blair – and 10 stayed put, one less than Starmer.

Yet the mood at the time was one of great disruption – with briefings about the so-called “shit list” kept by Johnson’s chief adviser Dominic Cummings naming the perm secs he wanted to oust, and the departures of Sir Philip Rutnam and Jonathan Slater in particular were highly controversial.

And even Blair's high proportion of change doesn't tell the whole story – it doesn't capture the disruptive force of high profile special advisers, for example, or the way in which some senior officials, such as Terry Burns at the Treasury, were sidelined despite remaining in post.

Davis explains that Burns was seen as too close to the Conservatives – with good reason since he had initially been appointed as the department's chief economic advisor because a previous Treasury perm sec, Douglas Wass, was perceived as a good administrator but unsympathetic to the monetarist policies of then-chancellor Geoffrey Howe.

Burns, like Wass before him, "gradually got sidelined, until very quietly, he left," Davis explains. Years later, Burns told Davis that his departure was a normal result of the need for a new style of working to reflect new leadership. "He told me, 'when you're part of the problem, it's time to go' and that a minister has got every right to want his or her leadership team the way that they wanted to be," Davis says.

While the large churn of perm secs – and shift in operating style – under the New Labour administration was noted as disruptive at the time, looking back, some officials characterise it as just another moment of generational shift. Speaking to Davis for a book on the period – Heroes or Villains, the Blair government reconsidered, co-authored with journalist John Rentoul – former Treasury official Nick MacPherson said that for those at the top of the Treasury the new way of working, including a greater role for special advisers, " was very novel but, if you were a younger person you thought 'fine this is just a new government with a new way of working'".

What about other prime ministers?

Theresa May, the only other PM to win an election in the last three decades, had the least upheaval, with just three departures in her first year in power and zero moves within government, which meant 18 of 21 perm secs stayed in their positions.

Of the three other PMs in the last three decades, Gordon Brown, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak – none of whom won elections – Truss's administration is perhaps most infamous for the sacking of Treasury perm sec Sir Tom Scholar on her first day in office. While her 50 days in power didn't see any further perm sec exits (although she did also sack her chancellor in that period), if she'd been in place for a year and got rid of perm secs at the same rate of one per 50 days then seven perm secs would have left, similar to the numbers for Starmer, Johnson, Cameron and Blair.

How has the change under Starmer affected the gender and ethnicity balance?

The gender balance is unchanged – there remain 12 male and nine female perm secs (including Defra interim perm sec David Hill), although the balance could change depending on who gets the perm sec position at Defra on a permanent basis.

The appointment of Emran Mian, however marked the moment when government once again has a perm sec on its books from an ethnic minority background, the first since Suma Chakrabarti departed in 2012.

What about second perm secs?

There has also been movement among the government’s second perm secs in Starmer's first 12 months, with several leaving, some of the positions being dropped altogether, and new ones being created.

The outgoings are:

- Crawford Falconer, DBT – left in December, won’t be replaced

- Paul Lincoln, MoD – left in March, won’t be replaced

- Nicholas Joicey, DBT – left temporarily on secondment in January to join Balvatnik School of Government as chief operating officer for a year

The incomings are:

- Michael Ellam, Cabinet Office – was chairman of public sector banking at HSBC. Became second perm sec, European Union and international economic affairs in January

- Tom Riordan, DHSC – was chief exec of Leeds City Council. Became second perm sec in September 2024

The other second perm secs across government are:

- Clive Maxwell, DESNZ

- Nick Dyer, FCDO

- Simon Ridley, Home Office

- Beth Russell, HMT

- Angela MacDonald, HMRC