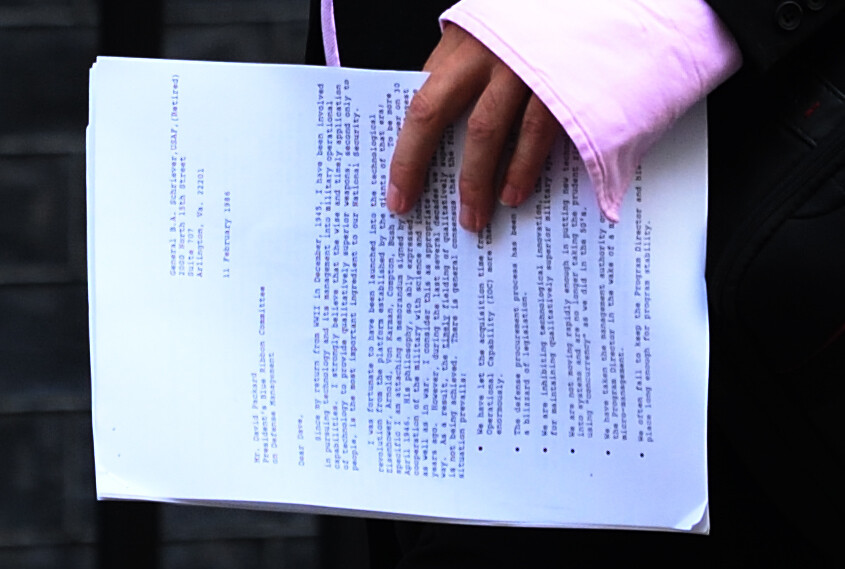

On his way to No.10 recently, Dominic Cummings was caught by photographers carrying in an old letter from a US air force commander Bernard Schriever, which expressed his anger at the “blizzard of legislation” hampering technological innovation. We should all be hoping this was statecraft and not accident. Because Brexit and the Integrated Review into foreign, defence and security policy is a one-off opportunity to re-write the rules on (government) competition, acquisition and procurement, crucial to our recovery and realising Cummings’ long-held ambition to make UK plc a genuine science and technology superpower.

Competition itself is not the problem: the principle objectives of the competitive process, fairness and value for money are vital. But competition can be unhealthy if the rules of the game, as currently set out by the EU, mean that businesses, researchers, governments and taxpayers all ultimately lose out. Our competition rules and processes lead to investments being made in technology projects that are outdated before they’ve even started.

Competition itself is not the problem: the principle objectives of the competitive process, fairness and value for money are vital. But competition can be unhealthy if the rules of the game, as currently set out by the EU, mean that businesses, researchers, governments and taxpayers all ultimately lose out. Our competition rules and processes lead to investments being made in technology projects that are outdated before they’ve even started.

Although the coronavirus pandemic has seen some rules loosened for procurement that is part of the Covid response, the usual rigid regulation means that large-scale technology projects often do not have the capacity to innovate. For a new aircraft carrier, new submarine or IT system, the emphasis is on black and white deliverables, budget and deadlines. There can often be an assumption that projects can be delivered in innovative ways with new technology, but in reality, they often just bring together existing, proven elements in order to manage risk. Locking in the spec from the start of tendering without the scope for contractual agility restricts innovation. End results are consequently mediocre, if not unsatisfactory.

Small and micro businesses with sharp new ideas, in particular, are at a real disadvantage. Through the existing research and development process, they might manage to attract initial funding to demonstrate the viability of their new technology or process, but that means nothing. Under existing competition rules the business has to start again when it comes to selling to a public body – the rigours of the R&D process and establishing a successful start-up isn’t taken into account and the traditional, burdensome acquisition process is initiated.

Most importantly, annual budget cycles in government can waste resources and make successful outcomes even less likely. Having to spend a fixed budget each year means that half the year is spent in a state of financial angst: three months at the end of the year worrying about the need to spend the residual money quickly to avoid budgets being cut; and three months at the beginning of the year trying to manage the carried over workload within the existing control total.

Innovation in this space is usually depicted as the product of an interdependent triangle: government, industry and academia working together. However, the barriers of the competitive processes mean we tend to have a vertical line instead: government and big business at one end, remote from the small and micro businesses and academic research at the other. There is no efficient link between the most enterprising new ideas and user/organisational needs.

No one wants to get rid of competition, we just need better competition. Taking the chance to re-write the rules post-Brexit; to make the triangle a reality: a free flow of funds across a diversity of players, start-ups and SMEs included, that gives innovation in technology, people and processes a chance to live through the ‘Valley of Death’ and have an impact.

In practice, the barriers to entry to large tendered contracts need to be lowered for those businesses that have already succeeded through government R&D programmes. There needs to be a switch to multi-year or lifetime budgeting for projects - often used successfully by the US Department of Defence; funding projects from cradle-to-grave without annual impediment and allowing for the kind of flexibility that leads to the best possible outcomes. To set projects free from deadening administration, we must move from cost control to outcomes focus where ‘success’ is measured by the net effect delivered rather than the completion of a project, and people must be incentivised accordingly. By making budgeting for risk a transparent part of process and being open to the ‘fail fast’ (or learning quickly) concept: doing everything in our power to avoid failures but accepting it as a vital part of the process, the community can learn and move on, stronger and better informed.

However, it’s not all about what government does. Small businesses simply cannot afford to bid for government contracts without support so it is vital that strategic partners are incentivised to adopt a responsible business ethos and act as honest brokers in mutually beneficial relationships. All stakeholders in businesses large and small, venture capitalists and accelerators need to be willing to contribute, to want to share a UK science and technology boom that is good for everyone, building together.

Competition itself is not the problem, but, for the moment, the competition game we are all being made to play is divisive and limiting the UK to some faulty or lacklustre outcomes.

Dr Simon Harwood is the head of defence and security at Cranfield University.