Anyone who has worked in government or any large organisation will have experienced frustration with a new system rollout. The technology itself might be great, but it often takes too long to get up to speed, isn’t intuitive, and becomes something you use only because you must, not because it makes your work easier.

At Hitachi Solutions, we believe technology should serve people, not the other way around. That’s why we embed a human-centric approach by default. This means designing solutions with the understanding that humans are complex, emotional, and varied in their interactions with systems and with other people using those systems.

Over the last six months, we’ve been digging deeper into what human-centric by default really means in practice. It’s a mindset we’ve brought to every conversation and project: from helping teams explore trauma-aware design, to supporting overstretched caseworkers through change, to questioning how digital sustainability and human well-being can sit side by side. Through our podcast series, we’ve started hearing from others who are wrestling with the same questions.

Why ‘human’ and not ‘user’ or ‘customer’?

The term ‘user’ is common in technology and design, and user-centricity is about making a service usable. Human-centricity, by contrast, is about understanding the context people are in when they use it. Thinking only about ‘users’ can commoditise the process: “How many users did you test with?”

‘Customer’ is also used in this area, but it’s not what we are looking for either, as it implies a transactional relationship where the information transition is the focus of the interaction, not the user.

‘Human’ is broader; it acknowledges that people bring emotions, physicality, and unpredictability into their interactions with technology.

One of the most powerful insights to come out of our podcasts is how trauma affects cognitive function. That means being human-centric isn’t just about kindness, it’s about being effective.

Someone who’s overwhelmed, anxious, or unsupported might struggle with even the most ‘accessible’ service. We need to ask deeper questions:

- Will this process create fear or friction for someone with bad past experiences?

- Are we designing for humans as they are, not as we imagine them to be?

- Are our tools and timelines realistic for people under strain?

Being human-centric by default means remembering that staff are humans too. The same pressures (fear of failure, cognitive overload, lack of control) affect the people delivering services, not just those receiving them.

Why By Default’ Matters

We’re realistic: you can’t always optimise for every human factor. Deadlines, legacy systems, and procurement rules are real constraints. But being human-centric by default means starting from the assumption that people matter most, and only compromising on that when you’ve got a clear reason.

That includes:

- Supporting people to learn and adapt, not just ‘use’.

- Taking time to explain why change is happening and how it will land.

- Thinking about long-term wellbeing, not just short-term transactions.

How can you make your process human-centric?

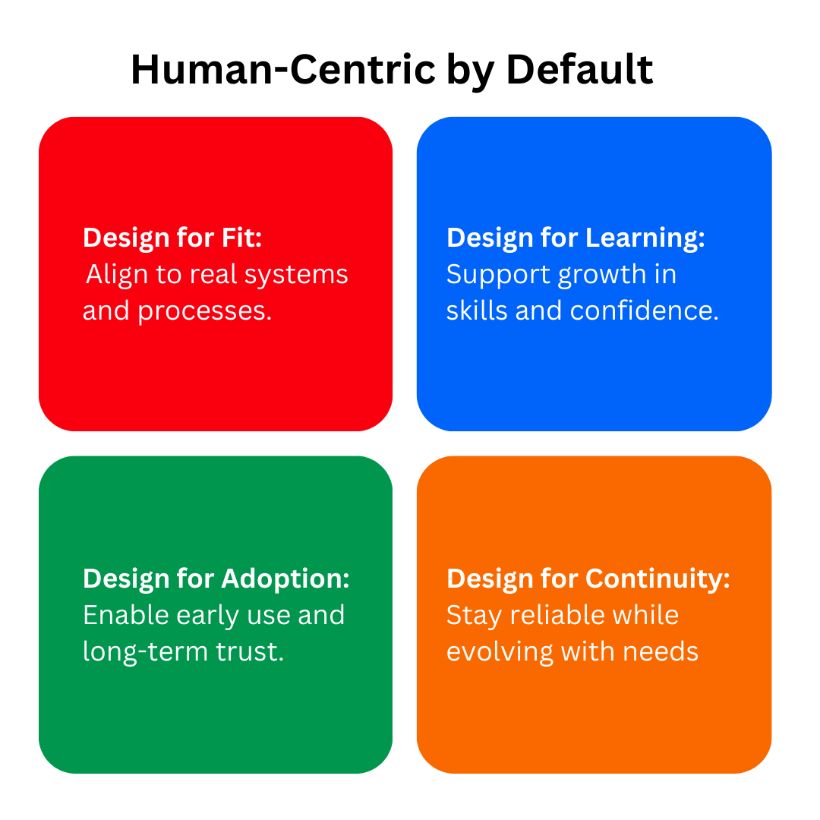

It’s useful to think about being Human-Centric through four different areas of focus.

Design for fit

The first step is to really understand the people involved. This means conducting research to identify who will use the system. It’s important to ask them not only what challenges they face and how technology can make their work easier, but also to gather a picture of how the system will fit into their wider working lives and culture.

Developing user personas, grounded in real behaviours and workflows and highlighting emotions and pressures, ensures that solutions are designed with empathy and relevance. The emotional and cognitive realities of work, stress, multitasking, and decision fatigue must be considered so that systems don’t just function well technically but also feel intuitive and reassuring to use.

Co-designing with employees and stakeholders (Humans) helps ensure the technology fits seamlessly into existing workflows rather than disrupting them. Interfaces should be intuitive, reducing cognitive load and frustration. Accessibility must be built in from the outset, ensuring that solutions work for a diverse range of people, including those with different levels of digital confidence or physical abilities.

Design for learning

To be truly effective, digital transformation needs to consider ease of adoption to ensure the workforce is equipped with the skills and environment to thrive.

Change is easier to embrace when people feel supported in building their skills. Training should fit naturally into the flow of work, rather than requiring people to step away from their day jobs.

Dedicated support, whether through super-users, coaching, or responsive helpdesks, helps people build confidence in new ways of working. This could mean short-form guides, walkthroughs embedded in the system itself, or recorded demos people can revisit. Encouraging peer learning, where those with more experience share approaches and shortcuts, can make adoption quicker and more sustainable. The aim is to build confidence through doing, not just through theory.

Design for adoption

Change can often feel overwhelming, so making it manageable and understandable is key to achieving efficiency and value. Clear, jargon-free communication ensures that people understand what’s changing and why to win over hearts and minds. Communication should be a two-way process, giving people a voice, answering their concerns, and adapting where necessary.

Smooth adoption depends on making first use positive and low-friction. Onboarding journeys need to be clear and supported by helpful, well-timed guidance. Early experiences should give people the confidence that they can succeed, and that the system is there to help them, not hinder them.

Design for continuity

Finally, the most successful transformations balance human and technological needs and consider whole-life usability. Technology needs to evolve over time to better meet the needs of the people using it, so bogging it down with customisation might initially give a great experience, but it will take its toll over time and will reduce the new shiny system to legacy tech very quickly. The goal is to balance usability with adaptability, so improvements can be made without undermining stability. Where automation or AI is used, it should enhance human decision-making rather than replacing it, ensuring people remain confident and in control.

People: The realities of human-centric design

We’re talking about human-centric design, so let’s focus on a couple of humans and how it could make their lives easier.

Alex, the Policy Officer

Alex, the Policy Officer

Alex works in a fast-paced government department, balancing policy development with responding to ministerial requests. A new data platform is introduced to streamline decision-making, but it requires multiple logins, a steep learning curve, and offers insights that don’t always align with real-world policy needs. The result? Alex finds workarounds, avoiding the system where possible, and productivity suffers.

A human-centric approach might:

- Design the system with Alex’s time constraints in mind, offering seamless integration and a simple interface.

- Provide contextual learning resources rather than lengthy, generic training modules.

- Ensure outputs align with the actual needs of policy teams, not just what the system can generate.

Priya, the Caseworker

Priya, the Caseworker

Priya processes applications for government funding. She deals with a high volume of cases, each with nuanced details. A new case management system promises efficiency but isn’t designed with her workflow in mind. The interface overwhelms her with unnecessary fields, and automated processes don’t account for the complexity of real cases. She ends up doing more manual work just to get around the system.

A human-centric approach might:

- Conduct real-world testing with caseworkers before deployment.

- Optimise automation to assist rather than replace human judgement.

- Offer flexibility so Priya can adjust workflows without breaking the system.

Building technology for humans, not just systems

Brilliantly crafted technical solutions can still fail the humans they are meant to support. Choosing to take a human-centric by-default approach instead means:

- Designing for messy realities, not ideal workflows.

- Recognising that stress, fatigue and fear affect how people read a screen, click a button, or ask for help.

- Choosing designs that support learning and adaptability, even if they’re less “slick” in the short term.

- Building trust by making things that feel usable, understandable and respectful.

At Hitachi Solutions, we design for the people behind the process. Because when people thrive, organisations succeed.

That’s what human-centric by default really means.

If this resonated with you, dive deeper into what it truly means to prioritise human-centric government in our podcast, Human-centric by default, hosted by Emma Charles, Industry Director for Government at Hitachi Solutions. Each episode features guests from across government and the public sector, exploring real-world challenges and insights around putting people at the heart of digital transformation.

Listen now on Spotify.

And, learn more about our government vision and solutions on the Hitachi Solutions UK website.

About the author

Emma Charles, Industry Director, Government for Hitachi Solutions

Emma is the Industry Director for Government at Hitachi Solutions. She is a digital transformation specialist with decades of experience in designing and managing high-profile digital change projects from both within and outside the civil service. Having started her career working with major world-class sports organisations, she has spent the past 20 years helping central government departments to improve their digital maturity, transformation effectiveness, and outcomes for citizens.